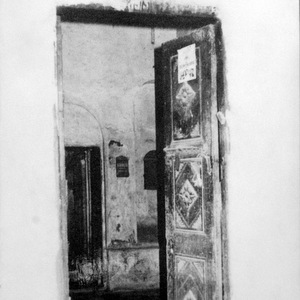

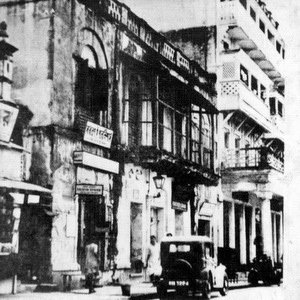

The house-search had continued all this while. It had started at five-thirty and eventually ended at about eleven-thirty. The all-encompassing house-search had included exercise books, letters, documents, scraps of paper, poems, plays, prose, essays - nothing had been excluded. Mr. Rakshit, a search-witness, seemed ill-at-ease; later, bemoaning his lot, he informed me that the police had dragged him along, without any prior intimation that he would have to be a party to such a distasteful activity. He narrated, in a most pitiable manner, the story of his kidnapping. The attitude of the other witness, Samarnath, was quite the opposite; he played out his part in the house-search as a true loyalist with great enthusiasm, as if to the manner born. There was no other mention-worthy event during the course of the search. But I recollect Mr. Clark examining the lump of earth from Dakshineshwar, preserved in a small cardboard box, with great suspicion; he suspected it might be some new and powerful explosive. In one sense, Mr. Clark's suspicions were not unfounded. Eventually it was concluded that the specimen was no different from normal earth and hence there was no need to send it for chemical analysis. I did not participate in the search except to open a few boxes. No documents or letters were shown or read out to me, except for one letter from Alakdhari, which Mr. Cregan read aloud as if for his own entertainment. Our friend, Benod Gupta, went marching around, shaking the room with each gentle foot-fall; he would bring out a document or letter from a shelf or some other place, and from time to time, exclaim "Very important, very important" and make an offering of it to Cregan. I was not made aware of what these "important" documents were. Nor did I have any curiosity in this regard, since I knew that it was impossible for any kind of formula for the manufacture of explosives or documents relating to conspiracy to be found in my house.

After turning my room inside-out the police moved on to the adjoining room. Cregan opened a box belonging to my youngest aunt, and after glancing at a couple of letters, promptly concluded that there was no need of carrying away the women's correspondence. Then the police mahatmas descended to the ground floor. Cregan had his tea there. I had a cup of cocoa and toast. Cregan took this opportunity to impress his political views upon me along with supporting arguments - I remained unmoved and bore this mental torture without a word. Physical torture may be a long-standing police tradition, but may I ask if such inhuman mental torture too is within the ambit of its unwritten law? I hope our highly respectable well-wisher Srijut Jogeshchandra Ghose will take up this question in the Legislative Assembly.

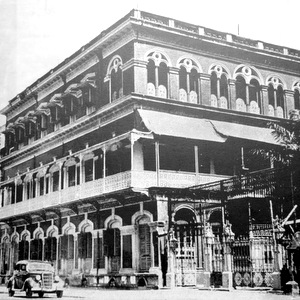

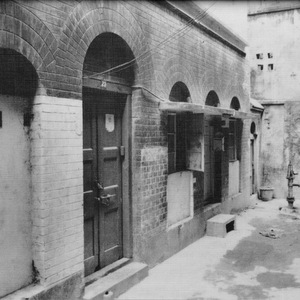

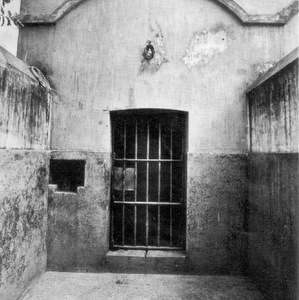

After completing their search of the rooms on the ground floor and the office of "Navashakti", the police came up to the first floor again to open an iron safe belonging to "Navashakti". After struggling with the safe for half-an-hour, they decided to carry it away to the police station. At this point a police officer discovered a bicycle with a railway label bearing the name of "Kushtia". The police immediately jumped to the conclusion that the bicycle must belong to the man who had earlier shot a sahib at "Kushtia" and gleefully took it away as a critical piece of evidence.

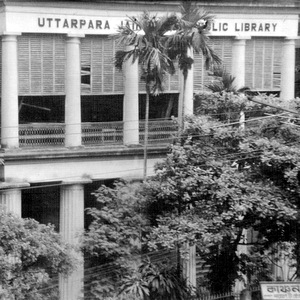

Views on House-Search as used in Bengal