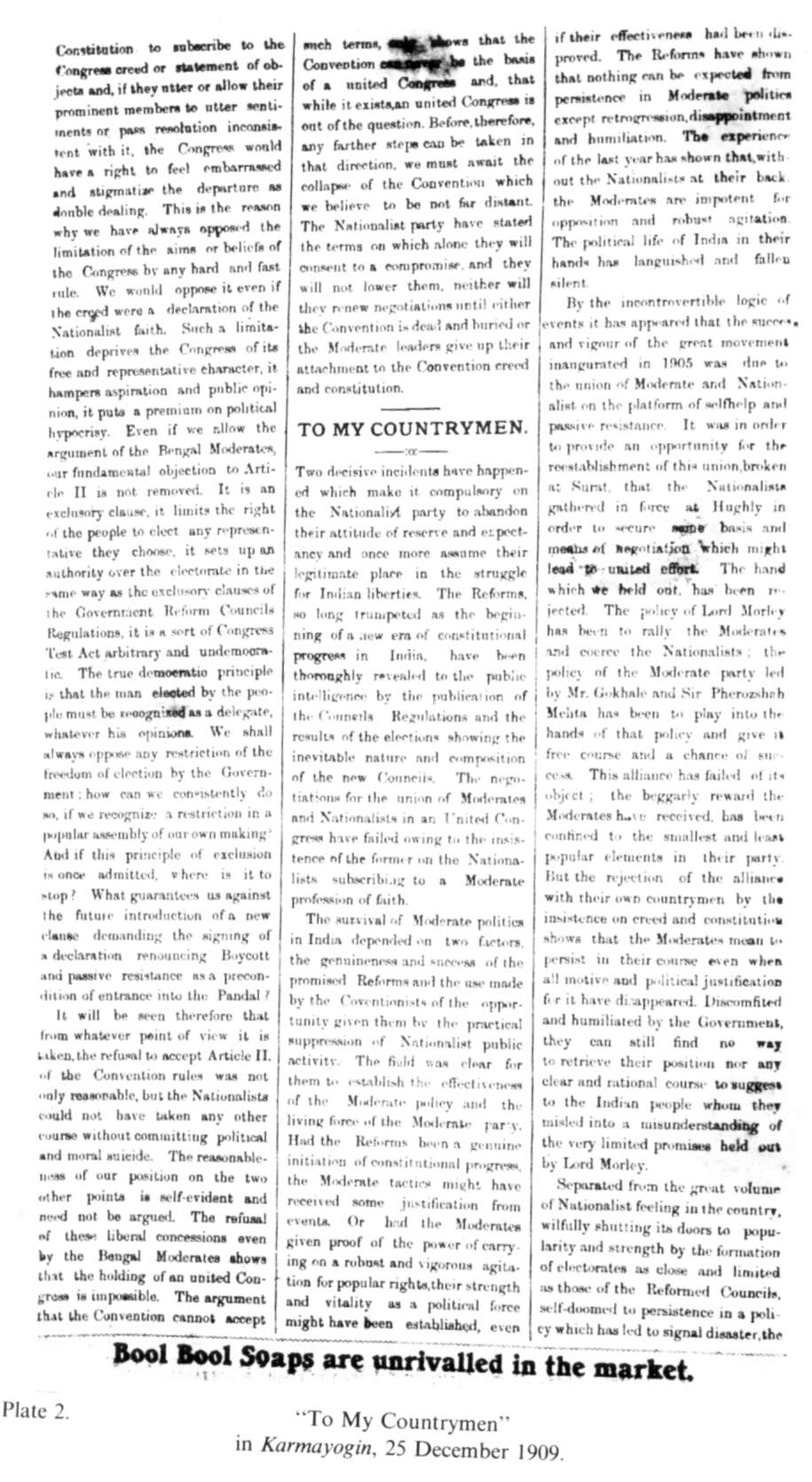

The survival of Moderate politics in India depended on two factors, the genuineness and success of the promised Reforms and the use made by the Conventionists of the opportunity given them by the practical suppression of Nationalist public activity. The field was clear for them to establish the effectiveness of the Moderate policy and the living force of the Moderate party. Had the Reforms been a genuine initiation of constitutional progress, the Moderate tactics might have received some justification from events. Or had the Moderates given proof of the power of carrying on a robust and vigorous agitation for popular rights, their strength and vitality as a political force might have been established, even if their effectiveness had been disproved. The Reforms have shown that nothing can be expected from persistence in Moderate politics except retrogression, disappointment and humiliation. The experience of the last year has shown that, without the Nationalists at their back, the Moderates are im-potent for opposition and robust agitation. The political life of India in their hands has languished and fallen silent.

By the incontrovertible logic of events it has appeared that the success and vigour of the great movement inaugurated in 1905 was due to the union of Moderate and Nationalist on the platform of self-help and passive resistance. It was in order to provide an opportunity for the reestablishment of this union, broken at Surat, that the Nationalists gathered in force at Hughly in order to secure some basis and means of negotiation which might lead to united effort. The hand which we held out, has been rejected. The policy of Lord Morley has been to rally the Moderates and coerce the Nationalists; the policy of the Moderate party led by Mr. Gokhale and Sir Pherozshah Mehta has been to play into the hands of that policy and give it free course and a chance of success. This alliance has failed of its object; the beggarly reward the Moderates have received, has been confined to the smallest and least popular elements in their party. But the rejection of the alliance with their own countrymen by the insistence on creed and constitution shows that the Moderates mean to persist in their course even when all motive and political justification for it have disappeared. Discomfited and humiliated by the Government, they can still find no way to retrieve their position nor any clear and rational course to suggest to the Indian people whom they misled into a misunderstanding of the very limited promises held out by Lord Morley.

Separated from the great volume of Nationalist feeling in the country, wilfully shutting its doors to popularity and strength by the formation of electorates as close and limited as those of the Reformed Councils, self-doomed to persistence in a policy which has led to signal disaster, the Convention is destined to perish of inanition and popular indifference, dislike and opposition. If the Nationalists stand back any longer, either the national movement will disappear or the void created will be filled by a sinister and violent activity. Neither result can be tolerated by men desirous of their country's development and freedom.

The period of waiting is over. We have two things made clear to us, first, that the future of the nation is in our hands, and, secondly, that from the Moderate party we can expect no cordial co-operation in building it. Whatever we do, we must do ourselves, in our own strength and courage. Let us then take up the work God has given us, like courageous, steadfast and patriotic men willing to sacrifice greatly and venture greatly because the mission also is great. If there are any unnerved by the fear of repression, let them stand aside. If there are any who think that by flattering Anglo-India or coquetting with English Liberalism they can dispense with the need of effort and the inevitability of peril, let them stand aside. If there are any who are ready to be satisfied with mean gains or unsubstantial concessions, let them stand aside. But all who deserve the name of Nationalists, must now come forward and take up their burden.

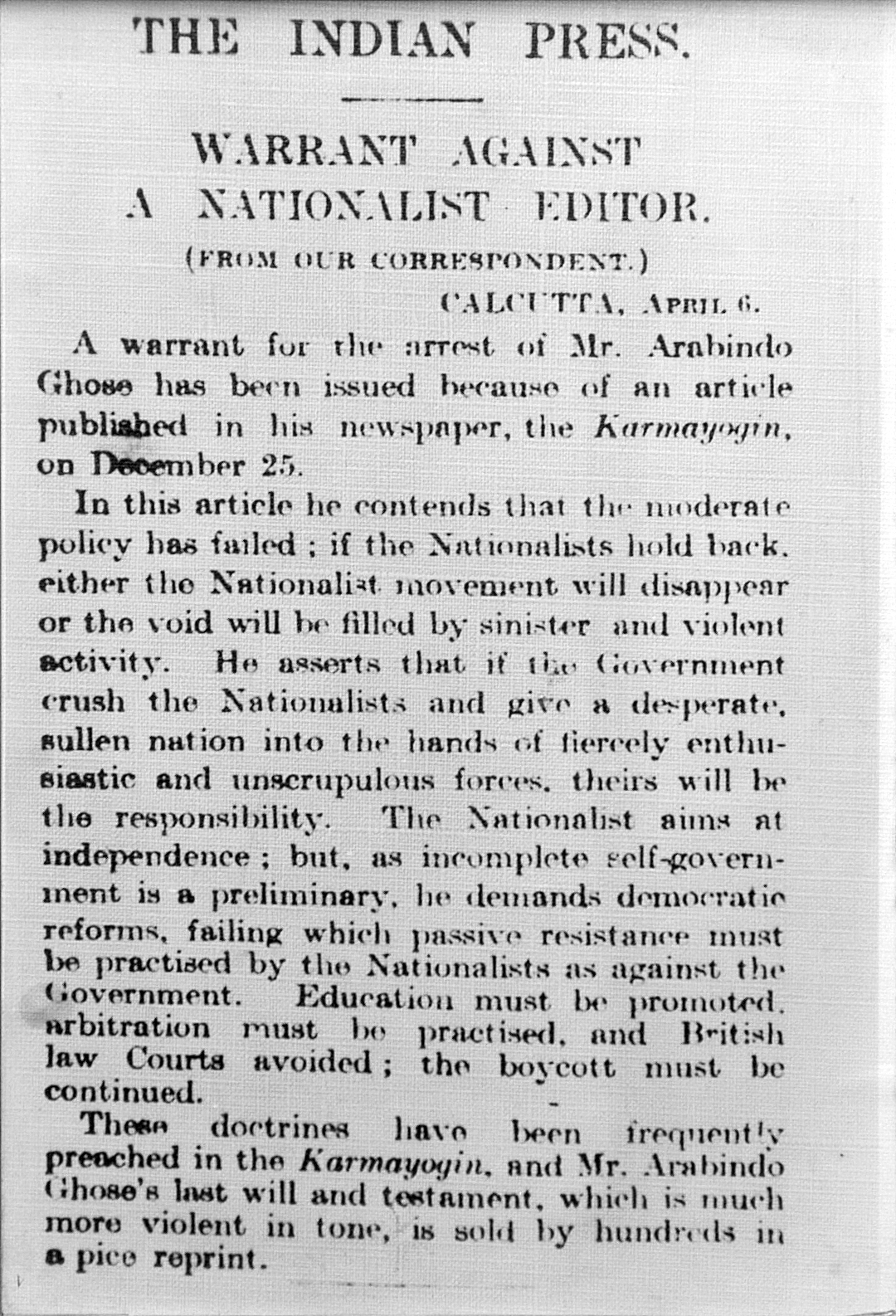

The fear of the law is for those who break the law. Our aims are great and honourable, free from stain or reproach, our methods are peaceful, though resolute and strenuous. We shall not break the law and, therefore, we need not fear the law. But if a corrupt police, unscrupulous officials or a partial judiciary make use of the honourable publicity of our political methods to harass the men who stand in front by illegal ukases, suborned and perjured evidence or unjust decisions, shall we shrink from the toll that we have to pay on our march to freedom? Shall we cower behind a petty secrecy or a dishonourable inactivity? We must have our associations, our organisations, our means of propaganda, and, if these are suppressed by arbitrary proclamations, we shall have done our duty by our motherland and not on us will rest any responsibility for the madness which crushes down open and lawful political activity in order to give a desperate and sullen nation into the hands of those fiercely enthusiastic and unscrupulous forces that have arisen among us inside and outside India. So long as any loophole is left for peaceful effort, we will not renounce the struggle. If the conditions are made difficult and almost impossible, can they be worse than those our countrymen have to contend against in the Transvaal? Or shall we, the flower of Indian culture and education, show less capacity and self-devotion than the coolies and shopkeepers who are there rejoicing to suffer for the honour of their nation and the welfare of their community?

What is it for which we strive? The perfect self-fulfilment of India and the independence which is the condition of self-fulfilment are our ultimate goal. In the meanwhile such imperfect self-development and such incomplete self-government as are possible in less favourable circumstances, must be attained as a preliminary to the more distant realisation. What we seek is to evolve self-government either through our own institutions or through those provided for us by the law of the land. No such evolution is possible by the latter means without some measure of administrative control. We demand, therefore, not the monstrous and misbegotten scheme which has just been brought into being, but a measure of reform based upon those democratic principles which are ignored in Lord Morley's Reforms, - a literate electorate without distinction of creed, nationality or caste, freedom of election unhampered by exclusory clauses, an effective voice in legislation and finance and some check upon an arbitrary executive. We demand also the gradual devolution of executive government out of the hands of the bureaucracy into those of the people. Until these demands are granted, we shall use the pressure of that refusal of co-operation which is termed passive resistance. We shall exercise that pressure within the limits allowed us by the law, but apart from that limitation the extent to which we shall use it, depends on expediency and the amount of resistance we have to overcome.

On our own side we have great and pressing problems to solve. National education languishes for want of moral stimulus, financial support, and emancipated brains keen and bold enough to grapple with the difficulties that hamper its organisation and progress. The movement of arbitration, successful in its inception, has been dropped as a result of repression. The Swadeshi-Boycott movement still moves by its own impetus, but its forward march has no longer the rapidity and organised irresistibility of forceful purpose which once swept it forward. Social problems are pressing upon us which we can no longer ignore. We must take up the organisation of knowledge in our country, neglected throughout the last century. We must free our social and economic development from the incubus of the litigious resort to the ruinously expensive British Courts. We must once more seek to push forward the movement toward economic self-sufficiency, industrial independence.

These are the objects for which we have to organise the national strength of India. On us falls the burden, in us alone there is the moral ardour, faith and readiness for sacrifice which can attempt and go far to accomplish the task. But the first requisite is the organisation of the Nationalist party. I invite that party in all the great centres of the country to take up the work and assist the leaders who will shortly meet to consider steps for the initiation of Nationalist activity. It is desirable to establish a Nationalist Council and hold a meeting of the body in March or April of the next year. It is necessary also to establish Nationalist Associations throughout the country. When we have done this, we shall be able to formulate our programme and assume our proper place in the political life of India.