Naren Goswami turns Approver

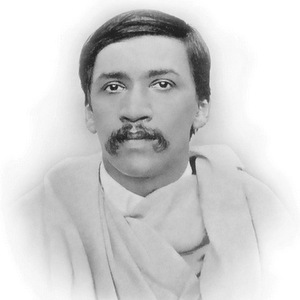

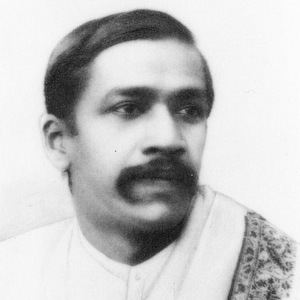

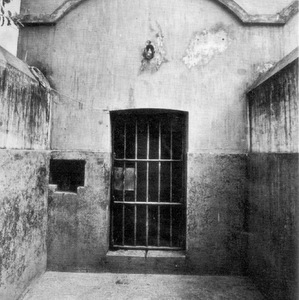

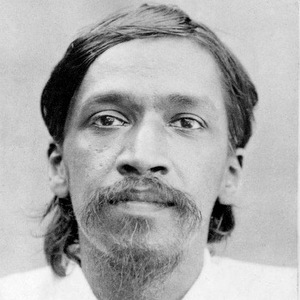

When we were detained in separate cells as part of solitary confinement, the only opportunity for brief conversation amongst ourselves was generally during the journey to the court in the police van or while waiting for the magistrate's arrival or during the tiffin-break. Those of us who already knew each other, spent every moment of this time in laughter, banter, pleasantries and discussion of all kinds, as if trying to make up for the time lost in the forced silence and solitude of the cell. I mostly limited my interaction to either Barindra or Abinash, as it was difficult to get acquainted or strike up a friendship with complete strangers in the prevailing circumstances. Hence, I would generally remain a passive participant in the conversation and laughter around me. However, there was one person who would sometimes try to strike up a conversation with me - this was none other Narendranath Goswami, who later turned into a State 'approver'. He was neither quiet nor well-behaved like the other boys but rather impudent, frivolous and unrestrained in character, speech and act. At the time of the arrest, his natural courage and boldness came to the fore but later on he found himself incapable of bearing even the slightest suffering and inconvenience of prison life. After all, he was a landlord's son, with a spoilt upbringing amidst luxury, pomp and moral indulgence. The severe austerity and constraints of prison life had driven him to despair and he expressed these feelings freely and openly to all. Gradually, he became possessed by an intense desire to escape the torturous conditions by any means possible. At first, he had hoped to retract his confession and prove that the Police had used physical torture to extract a confession of guilt from him. He mentioned that his father was determined to make requisite arrangements for false witnesses. A few days later, a new aspect was revealed to us. His father and a moktar (a pleader's agent) began to visit him frequently in the prison. Eventually detective Shamsul Alam also started holding long conversations with him in secret. During this period, Gossain's inquisitiveness and prying questions led to a preponderance of suspicion in the minds of many amongst us. He would ask many kinds of questions of Barindra and Upendra, regarding their acquaintance with or closeness to important Indian personalities, the identity of those who nourished the secret society with financial assistance, the identity of other members outside India or in other provinces of India, the next rung of leadership who would run the society and the location of other branches of the society. Soon, everyone came to know of Gossain's thirst for information and his trysts with Shamsul Alam and their growing intimacy too became an open secret. All of this was analyzed in detail and it was noticed by some that after every such darshan (visit) by the police, Gossain seemed to discover a fresh set of questions. It is needless to mention that Gossain did not receive satisfactory answers to any of his questions. When this matter first came to light, Gossain confessed that the police were trying to persuade him to turn "King's Witness". He once mentioned this matter to me in the court. I asked him: "What has been your response?" He said: "Am I going to fall for that! And even if I do agree, how much do I really know, to give the kind of evidence they want me to?" After a few days, when he broached the subject once again, I noticed that things had advanced substantially. He was standing by my side at the identification parade when he said, "The police repeatedly visit me." I told him jokingly: "Why don't you tell them that Sir Andrew Frazer was the chief patron of the secret society - that should make their persistence worth its while". Gossain responded: "I have indeed said something on these very lines. I have told them that Surendranath Banerji is our head and that I had once shown him a bomb." I was staggered at this disclosure and asked him: "Was there any need of saying such a thing?" Gossain responded: "I will send these ... to an early grave. I have fed them many such things. They will perish in trying to find corroboration. Who knows, the trial might be held up because of this." I only said this in response: "You should give up this kind of mischief. If you try to be too clever with them, you will end up being deceived yourself." I do not know the degree of truth in Gossain's words. The general belief amongst the accused was that Gossain was trying to mislead us by saying all this. My own sense was that Gossain had not yet committed himself to the idea of turning an 'approver'. Although he was leaning more and more in that direction, he also nurtured hopes of damaging the Police case by misleading them. The ones of a wicked disposition are naturally inclined to achieve their ends through deception and dishonesty. It became evident to me that the Police now held sway over Gossain and he would say or do anything under their influence to save his own skin. The degradation of a base nature through successively more ignoble acts was being enacted before our very eyes like the acts of a play. I noticed the changes in Gossain's mental make-up, his appearance, his expression and mannerisms and even in his speech. In order to justify his treachery, he would devise various kinds of economic and political pretexts from time to time. It is not very often that one gets first-hand access to such an interesting psychological study.

At first, we did not let Gossain know that his deception lay exposed to us. He too was stupid enough not to realize this for quite some time and imagined that he was helping the police in complete secrecy. But after a few days, orders were passed to keep all of us together instead of keeping some separately in solitary confinement. In this new arrangement, where people could mix and converse freely with each other, it was very difficult to keep the facade. During this phase, quarrels broke out between Gossain and a couple of the boys and Gossain was able to infer from their words and the generally unpleasant treatment from everyone around that his deception was no longer a secret. Later on, when he gave his evidence before the court, some English newspapers reported that this unexpected event had caused surprise and excitement amongst the accused. Needless to say, this report was based entirely on the imagination of the reporters. We had guessed well in advance the manner and nature of evidence that would be provided in court. In fact, even the date on which the evidence would be given was known to us. During this time, an accused went to Gossain and said - "Look, brother, life here is intolerable. I too would like to turn an 'approver'. Please tell Shamsul Alam to arrange for my release." Gossain agreed to this and after a few days, he informed the convict that a favourable consideration of his request was likely and a letter from the government had been issued to that effect. Gossain then asked the convict to eke out some important information like the location of the branches of the secret society and the identity of its leaders from Upen and the others. The make-believe 'approver' was a mischievous person with a sense of humour. He consulted with Upendra and then provided a set of imaginary names to Gossain as the said leaders of the secret society: Vishambhar Pillay in Madras, Purushottam Natekar at Satara, Professor Bhatt in Bombay and Krishnajirao Bhao of Baroda. Gossain was delighted and conveyed this 'reliable' information to the police. The police on their part searched every nook and cranny of Madras, and found many Pillays, of various shapes and sizes, but none that also answered to the name of Vishambhar or even half of it. As for Satara's Purushottam Natekar, he kept himself shrouded in utmost secrecy. In Bombay, a certain Professor Bhatt was discovered, but he turned out to be a harmless gentleman. Since he was a loyalist to the Crown, it was inconceivable that he could be linked to any secret society. Yet Gossain based his evidence upon this very hearsay from Upen and made a sacrificial offering of Vishambhar Pillay and other fictional leaders of the conspiracy at the holy feet of Norton to strengthen his made-up prosecution case. The police added to the mystery around Bir Krishnajirao Bhao by producing the copy of a telegram sent to Krishnajirao Deshpande of Baroda by some 'Ghose' from the Manicktola Gardens. The people of Baroda were unable to confirm the existence of anyone answering to that name, but since Gossain, the very epitome of truthfulness, had spoken of a Krishnajirao Bhao of Baroda, then surely Krishnajirao Bhao and Krishnajirao Deshpande must be the same person. The name of our respected friend, Keshavrao Deshpande, had already been discovered in my correspondence. Therefore, it hardly mattered whether Krishnajirao Deshpande really existed or not and it could not but be that Krishnajirao Bhao, Krishnajirao Deshpande and Keshavrao Deshpande were all names of the same person. This proved that Keshavrao Deshpande was a leader of the secret conspiracy. Such extraordinary inferences formed the basis for Mr. Norton's infamous prosecution theory.

Gossain claimed that it was at his instance that our solitary confinement ended. According to him, the police had made arrangements for us to be together in larger groups so that he could stay amidst us and glean secret information related to the conspiracy. Gossain did not realize that we were aware of his new-found vocation and continued with his probing questions regarding the identity of those engaged in the conspiracy, the locations of other branches of the secret society, the identity of the patrons and financial contributors, the identity of those who would now be in charge of the secret society and other enquiries on the same line. I have already given examples of the kind of responses he received. But a majority of Gossain's assertions turned out to be untrue. Dr. Daly had informed us that it was he who had persuaded Emerson sahib to allow this change in our accommodations. It is possible that Daly's version was correct and on being informed about the change, the police may have sought to benefit from the new arrangement in the manner Gossain had described. Be as it may, everyone welcomed this change except me; I was reluctant to be in the company of other men, as my sadhana was progressing rapidly during that period. I had had a fore-taste of samata (equality), 'desirelessness' and peace, but these states had not yet been fully established in the being. I was apprehensive that the new consciousness may diminish and even be subsumed in the company of other men or if my nascent condition was prematurely exposed to thought-waves of other persons. In fact that is exactly what happened. I understood only later that it was necessary to raise the opposing state for the completeness of my realization. Hence, the Antaryamin (Inner Guide) suddenly brought me out of solitude and flung me into an overpowering stream of outward activity. The rest of the group however found it difficult to contain their joy at this turn of events. That night everyone gathered in the largest room, in which singers like Hemchandra Das, Sachindra Sen were already resident and no one slept till two or three in the morning. That night, the silent prison reverberated with the ring of laughter, the endless stream of songs and the pent-up stories that were flowing like flooded rivers in the rainy season. We fell asleep but every time we woke up, we heard the laughter, the singing and the conversation continuing unabated. In the early hours of the morning the stream thinned out. The singers too fell asleep and our wards fell silent.